By Regina Bechtle, SC

By Regina Bechtle, SC

In September, 1809, soon after Mother Seton began her community in Maryland, Rev. Anthony Kohlmann, S.J., administrator of the New York diocese, wrote to her with the hope that she would eventually send “a small colony of your Holy Order” back to her native city to provide education for girls.

That hope wasn’t realized for eight more years. In July, 1817, Bishop John Connolly of New York formally asked Elizabeth for Sisters to open and staff an orphanage. Lay Catholics like Francis Cooper, Robert Fox, and Cornelius Heeney saw the need, incorporated the “Roman Catholic Benevolent Society,” and prodded the bishop to ask for Sisters to “regulate and instruct” the orphans. “It would be productive of a great deal of good here,” Bishop Connolly wrote, prophetically.

The Rev. John Dubois, canonical superior of the Sisters, made sure that the bishop understood the conditions under which Sisters would be sent:

- The trustees would be responsible for all financial accounts and decisions, but the Sisters would be “permitted to manage the interior of the house in their own way, according to their Rules.”

- A Ladies Society would be formed to “forward the interests of the Institution” (i.e., raise funds).

- The Sisters would be allotted $36 annually for their clothing, so no one could accuse them of using any money that had been collected for the orphans’ support.

- The Sister Superior would be consulted regarding any change in the number of orphans, as well as their admission or removal.

- The trustees would pay the travel expenses of Sisters to and from Emmitsburg, if it had to do with orphanage business.

Lastly, Fr. Dubois stated that, because the New York asylum, like the one in Philadelphia, required a “zealous, prudent, economical mother to govern it,” Sister Rose White would be transferred from Philadelphia to fill the role in New York. Her experience would be invaluable for this new mission of Charity, and she was eminently suited to guide “younger and healthy Sisters … to perform the laborious work of the establishment.”

In early August, 1817, Mother Seton wrote to an adviser, “…the desire of my heart and Soul for her [Rose] going to New York has been long pressing for so much must depend as says the good gentlemen who write about it on who is sent to my ‘native city’ they say, not knowing that I am a citizen of the world.” Earlier, Archbishop Carroll of Baltimore had commented, “New York is a city of too much consequence not to demand superior abilities.”

Sisters Cecilia O’Conway and Felicité Brady were the two “younger and healthy” souls whom Mother Seton chose for the New York mission. They left Emmitsburg August 13, 1817 (probably escorted by Mr. Robert Fox, whose daughters attended the school), met Rose White in Philadelphia, and continued on, arriving in New York August 20, 1817.

Because the house that was supposed to be “fit to receive some orphans” in July was not yet ready for them, the Sisters spent their first few weeks in the home of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Fox at 89 Washington Street. The family knew the Sisters well since the Fox girls were students at St. Joseph’s Academy in Emmitsburg. Mother Seton thanked Mrs. Fox for her gracious hospitality to the “three beings most dear to me in our God” who were no doubt overwhelmed by a city that was, even in 1817, the most populated in the country.

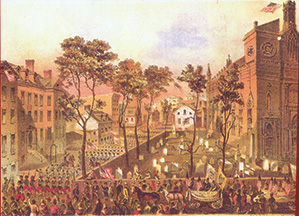

The Strangers’ Guide for 1817 gave a contemporary view of the city which the first three Sisters—none of them native New Yorkers—encountered:

In extent New-York city measures in length, from the West Battery to Thirty-first street, about four miles; and in breadth about one and a half miles. Its circuit is eight miles. The whole of this space is not yet covered with buildings but the greater portion of it is, and it is probable, as new houses are rapidly appearing, that the plan of the city will be filled up within the course of a few years. The number of Dwelling Houses is estimated at 17,000. The population exceeds 100,000 which gives about six inhabitants to each house….The Streets of New-York, including Lanes and Alleys, amount to 252. Almost the whole city is well lighted with lamps….A regular night watch is also established to give security to the inhabitants.

(Walsh I, 47-48, ALSO SEE Walsh I, 47 ff – Young New York)

What The Strangers’ Guide failed to note was the grinding poverty, filth, and stench of a city that did not yet have paved streets, waste management, or reliably safe drinking water. Christine Stansell, a scholar of our day, describes the brutal winters, recurring economic downturns, massive waves of immigrants, and yearly outbreaks of yellow fever and other diseases that marked life in New York in the early part of the nineteenth century. No wonder Elizabeth Seton once described New York as “so distracted a place.”