During times of great challenge, inspiration may be sought by examining the trials and lessons of historic events. While the devastation of the coronavirus COVID-19 extends globally, in the United States the epicenter is New York City. With the prospect of an overwhelming need for hospitalizations during this pandemic, a temporary hospital facility has been established in Central Park; this is not the first such hospital. The annals of the archives of the Sisters of Charity of New York reveal that 158 years ago, the first hospital facility in Central Park was housed in the first Motherhouse for the Congregation, staffed by its sisters.

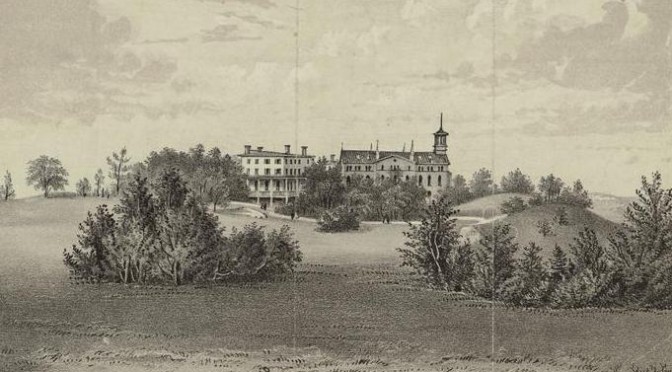

When thirty-three Sisters of Charity serving in New York, separated from the founding community in Emmitsburg, Maryland, in 1846, Mother Elizabeth Boyle purchased a seven-acre Manhattan property at McGown’s Pass for $6,000, which today would be located between 102nd and 107th Streets along Fifth Avenue. A building to contain classrooms, study and recreation halls was built in 1850, and, in 1855, a large brick structure to include a chapel and dining rooms was built. During that same year, however, a law passed in 1853 was enacted to build a Central Park from 59th Street to 106th Street. In 1856, all residents within the boundaries of the proposed park were ordered to vacate the premises. The Commissioners of Central Park paid $135,000 for the original Mount Saint Vincent property. After less than one decade, the sisters re-located from McGown’s Pass to Font Hill-on-Hudson, north of Manhattan in the Bronx.

Although few current members currently serve in direct patient care, during their over 200-year history, the Sisters of Charity of New York have been called to respond to the urgent needs of medical crises. St. Vincent’s Hospital, formerly in lower Manhattan (1849-2010), was founded by the Congregation to treat the poorest victims of the cholera epidemic. From 1862 and throughout the Civil War years until 1867, Sr. Ulrica O’Reilly and a group of 14 fearless sisters cared for the returning, wounded soldiers in a temporary military hospital at the former Motherhouse building in Central Park.[1]

The New York City Council determined that the empty Mount Saint Vincent buildings could be converted to a military hospital. Mr. Edwards Pierpont, member of the Union Defense Committee, penned his recommendations that the Sisters of Charity of New York staff the hospital. In a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton dated September 9th, 1862, he wrote:

The New York City Council determined that the empty Mount Saint Vincent buildings could be converted to a military hospital. Mr. Edwards Pierpont, member of the Union Defense Committee, penned his recommendations that the Sisters of Charity of New York staff the hospital. In a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton dated September 9th, 1862, he wrote:

“The Commissioners of Central Park of this city have given a very large building for a Government Hospital for the reception of wounded soldiers. This building was formerly a Catholic school of high order. “The point is this: we want the nurses of this hospital to be the Sisters of Charity, the most faithful nurses in the world. Their tenderness, their knowledge, and religious convictions of duty render the by far the best nurses around the sick bed which have ever been found on earth. All that is asked is that they be permitted to nurse under the direction of the War Department and its physicians.” [2]

In agreement, United States Surgeon General Joseph R. Smith forwarded an immediate response to Surgeon Charles McDougell, New York City, dated September 10, 1862:

…“The building will be very gladly received and fitted up as a hospital. The Medical Director at New York will be at once instructed to receive it. No one can bear fuller or more willing testimony to the capability and devotion of the Sisters of Charity than myself. Several hundred are now on duty as Nurses under my charge. Those referred to within will also be accepted thankfully.” [3]

Mother Mary Jerome Ely sent 15 sisters to the military hospital at the former Motherhouse to care for wounded Civil War soldiers.

Upon their request, Mother Mary Jerome Ely sent the group of 15, all who had volunteered their service and all but one who had taken their vows at their former home at McGown’s Pass, from their home at Font Hill-on-Hudson, Bronx, to the vacated Motherhouse. Despite formal medical training, the Sisters of Charity were trusted to provide nursing care, a testament to their extensive hospital and administrative experience, and a willingness to follow orders. Sr. Mary Ulrica O’Reilly, Superior, named to head the hospital, had extensive medical experience in crisis management at St. Vincent’s Hospital. [4] The sisters sent on mission with her used the skills acquired during their years caring for children at orphan asylums, for the elderly impoverished, and for patients at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

In the former Motherhouse building, the spacious dormitories, corridors, halls, refectories, assembly rooms, porches, and chapel could house 250 patients in thirteen wards. The chapel, or Ward 1, was dedicated to the care of the most extreme cases. [5] Although planned to treat amputees, multiple afflictions prevailed. Patients harboring symptoms of tuberculosis, rheumatic fever dysentery and contagious illnesses, were treated in separate isolated tents on the grounds. [6]

Informally referred to as Mother Jerome’s Hospital, The Central Park General Hospital or St. Joseph’s Government Hospital, St. Joseph’s Military Hospital was noted as one of “twelve places in New York for the reception and care of sick and wounded soldiers.” [7] On October 28, 1862, the first 120 arrivals brought by train from battlefield hospitals were met by the sisters; only one patient was known to be Catholic. [8] In addition to distributing medical supplies, dressing wounds, dispensing medication, and feeding and washing patients, the sisters assisted the surgeons with amputations and other medical procedures. Imparting their devotion, the sisters provided spiritual comfort, encouraged the dying to seek God’s forgiveness, baptized those who wished, and prepared the dead for religious burial.

Several vignettes describe the sisters’ immeasurable devotion to caring for the physical and emotional well-being of the soldiers:

Prior to Thanksgiving in 1862 Sr. Ulrica O’Reilly, wrote to request permission to provide a season meal of familiar delicacy for the men, Surgeon-in-Charge Frank H. Hamilton allowed her request, also recommending, “that as their condition will not allow the partaking of many of those articles of diet which are usually furnished on such an occasion, since the dinner must be, after all, very plain, that you do not announce your intention to them…” [9]

To the great delight of the soldiers, Sr. Ulrica did serve a more sumptuous meal than was approved. Shortly thereafter on December 1, 1862, Sr. Ulrica received this brief reprimand: “All purchases for the Hospital will be made hereafter by the Steward. By order of Frank H. Hamilton, Surgeon-in-Charge. “[10]

When protestors during the Draft Riots of 1863 threatened to attack the Hospital, Sr. Ulrica interrupted her duties to confront the mob wielding fire torches. As she faced the angry men gathered at the door, she calmly informed them that the sisters would not leave the Hospital as demanded, that they would not abandon their patients. Impressively, the men dispersed and left the premises without harm to anyone. [11]

Union soldier Captain William Seton, wounded at Antietam in September 1862, was transferred to St. Joseph Military Hospital and cared for by Sr. Ulrica. As all soldier patients were assigned identification numbers to maintain anonymity, Sr. Ulrica did not realize that one of the soldiers was the grandson of foundress Elizabeth Seton, until after his recovery. [12]

The sisters also cared for the teenaged buglers and drummers, who volunteered their service alongside the troops. [13] The boys, too young to be without the comfort of a parent, were in a separate ward from the adults to allow them emotional privacy. Most poignant is the description of a young sister, who brought home-made candy and cakes for the boys. Called “The Irish Nightingale” because of her beautiful voice, every evening the sister sang popular war tunes to the accompaniment of her guitar. “Better than medicine,” the doctors commented. [14]

During the Civil War years 1861-1865, over 30,000 wounded soldiers were treated in hospitals in Manhattan, Brooklyn and New Jersey. [15] When the war ended, the sisters continued their services at the Hospital until the last patient was discharged in 1867. Tragically, several sisters contracted illnesses during their service and died. Sr. Mary Prudentia Bradley, the only novice at the Hospital, pronounced her vows on her deathbed. [16]

Careful inspection of Sr. Mary Ulrica O’Reilly’s tombstone reveals the Army Cross. The most visible aspect is the bottom point.

Fifty years later, five of the fourteen Sisters of Charity who served in the Civil War as army nurses were honored posthumously. Government markers were placed on these sisters’ graves in the Cemetery of Mount Saint Vincent, Bronx: Sr. Mary Rosina Wightman, Sr. Mary Ulrica O’Reilly, Sr. Ann Cecilia Nealis, Sr. Mary Columba Lawrence and Sr. Mary Perpetua Drumgoole. In 1922, the other nine sisters who served and are buried elsewhere, were acknowledged when government tombstones were received: Sr. Mary Christine Meyers; Sr. Mary Teresa McCloskey; Sr. Mary Justine McGlynn; Sr. Mary Francesca Molitor; Sr. Mary Genevieve McCormack; Sr. Mary Antoinette Kelly; Sr. Ann Scholastica Quinn; Sr. Mary Emerentia Hanaway, and Sr. Francis Assisium Madden. [17]

After the war, the Park’s Commissioners maintained administrative offices in some of the buildings and one of the former Mount Saint Vincent buildings became a hotel with restaurant, known as Stetson’s Hotel. The convent chapel was used to house an art gallery, museum, with an outdoor pavilion. [18]

On the morning of January 2, 1881, the building was destroyed by fire, said to have been caused by a defective fireplace. The firefighters were thwarted in combating the blaze by having to drag their equipment over the hills and “much precious time was lost in digging to the hydrants, which were set beneath the ground.”[19] In June of that year, the Park’s Commissioners ordered the ruins cleared, and leveled the area planted with creeping vines. In 1883, a tavern was built which became known as McGown’s Pass Tavern. The area continued to be known as “Mount Saint Vincent” despite the sisters’ departure many years prior to Mount Saint Vincent-on-Hudson in the Bronx. To avoid confusion, Mother Mary Jerome Ely requested the name “Mount Saint Vincent” be removed from the map of Central Park on Apri1 16, 1884. [20] From then on the area was referred to as McGown’s Pass.

In today’s Central Park, at the approximate location of the former Mount Saint Vincent at McGown’s Pass, a plaque embedded in a stone marker bears the inscription: “Near this site along the old Kingsbridge Road stood the first Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity, Saint Vincent de Paul of New York and the Academy of Mount Saint Vincent, 1847–1859. [21]

By Mindy S. Gordon

Director, Archives and Museum

NOTES

- Walsh, Sr. Marie De Lourdes Walsh. The Sisters of Charity of New York, 1809-1959. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1959), Vol. III, p. 174.

- Edwards Pierpont to Edwin Stanton, September 9, 1862. Archives, Sisters of Charity of New York. Record Group 401, Academy of Mount Saint Vincent, Box 2A.

- General Joseph R. Smith to Surgeon Charles McDougell, September 10, 1862. Archives, Sisters of Charity of New York. Record Group 401, Academy of Mount Saint Vincent, Box 2A.

- John Freund, CM. Sisters of Charity of New York and the Civil War Vincentian Family, April 4, 2014. https://famvin.org/en/2014/04/04/sisters-charity-ny-civil-war/

- Edward K. Spann. Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865 (Wilmington: SR Books, 2002), p. 79.

- Walsh, Vol. III, p. 170.

- Ibid, Vol. III, p. 170.

- Courtney, Sr. Anne. Pioneer Sisters of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Manuscript, 1995.

- Walsh, Vol. III, p. 172.

- Ibid, Vol. III, p. 173.

- John Freund, CM. Sisters of Charity of New York and the Civil War Vincentian Family, April 4, 2014. https://famvin.org/en/2014/04/04/sisters-charity-ny-civil-war/

- Courtney, Sr. Anne. Pioneer Sisters of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Manuscript, 1995.

- “Distinguished Service in Civil War Recalled” by Thomas E. Kissling. The Tablet: June 10, 1961.

- Walsh, Vol. III, p. 173.

- Edward K. Spann. Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865 (Wilmington: SR Books, 2002).

- Walsh, Vol. III, p. 174.

- “Graves of War Nurses Marked,” Hospital Progress, Official Magazine of the Catholic Hospital Association of the United States and Canada, III, (1922).

- Hall, Edward Hagaman. McGown’s Pass and Vicinity: A Sketch of the Most Interesting Scenic and Historic Section of Central Park in the City of New York. (Central Park, New York, New York: American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1905, p. 41.

- Vincentian Family Media Network: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433035185127&view=1up&seq=66

- “A Notable Fire: Mt. St. Vincent Burned to the Ground, A Park Attraction Gone,” New York Herald, January 3, 1881, p. 3D, https://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html.

- https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/central-park/monuments/1921

- Hall, Edward Hagaman, p. 42.

Images of Mount Saint Vincent in Manhattan: https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2011/06/mysterious-central-park-convent-mount.html

What a wonderful article! Thanks for sharing this rich history of charity.

Thank you for the interesting article about the Sisters of Charity and the hospital that once stood in Central Park. The history was information I had not heard before. It brought a smile to my face reading two examples of determination: (1) insuring the patients got a good and special meal on a special occasion despite objections to the cost of this; and (2) . when a mob carrying torches pressured Sister to leave the hospital and she stood up to them refusing to leave because she insisted upon caring for the patients. I smile because that is the determination I saw in the wonderful Sisters of Charity who taught me at SVH-Staten Island. I often think of how they modelled faith, hope, and charity and also how determined they were in protecting and providing for those who needed their help most – the elderly and the poor. Again, thank you for that wonderful story! The vines of Tavern on the Green have taken on a new meaning for me!

Fact-filled, account of these fearless, giving Sisters, So many interesting anecdotes in this fascinating history. And, glad to read they were honored for their selflessness. A beautiful homage in their honor. Bravo!

Thank you for the illuminating and interesting history lesson.

What a wonderful article. Thank you for providing all this information at this time.

This is a fascinating article. It reinforces for me the fact that the Sisters of Charity played an integral role in the history and development of New York City.